Looking back in time: Bali in the 30s

Part 1

After the premiere of the rediscovered and restored film Island of Demons (1933) in Usada August 2nd, 2025, we interviewed Balinese audience about their impression.

Maha Dewi:

As a Balinese, the film brings back memories of my time with my grandpa. All the traditions and culture I’ve known since I was a child—it goes back far before I was born. I was born in Bona, which is very close to where the film was shot, in Bedulu. The film feels authentic to a large extent. It also makes me a little sad, because so much has changed in Bali. It’s not like it used to be—not like in my grandfather’s or even my father’s time. I’m grateful to see the old Bali in the film.

And the dialect used—it’s quite an old Balinese dialect, probably specific to the Bedulu area. Bona and Bedulu are in the same district, so we share the same dialect, but the one used in the film is really old. It’s from my grandfather’s time—he was born in the 1930s and even earlier. It’s not spoken that way anymore.

As we discussed before, from a Balinese perspective, it’s easy to distinguish between European influence and what is truly Balinese. For me, what’s really Balinese is in the expressions and activities. On the other hand, the music in the film was more European. In Bali, we mainly use Gamelan music. The European music helped to express emotion differently. It acted like a translator—it expressed feelings in a way Europeans might understand. But in my culture, I can follow the Balinese storyline without needing that kind of music.

film stills “Island of demons” 1933, Director Friedrich Dalsheim (c) Kinemathek Berlin

Maha Dewi: And the depiction of Rangda, as we mentioned, from a Balinese point of view, is more about balance. Yes, I agree.

Interviewer:

Yes, it’s interesting how strong the European perspective is—how the witch has to die in the script by European authors.

Maha Dewi:

We’re more focused on balancing, like Yin and Yang, black and white. We’re not trying to say one energy is higher or lower than the other. We try to keep everything balanced. I’ve heard stories about a witch, or Rangda, where people give offerings—not to destroy her, but to maintain a good relationship. But the Western perspective often sees the witch only as something bad.

However, both the priest and the witch possess the same knowledge—it’s just used differently. And to me, it’s still the same knowledge.

Interviewer:

That’s an important lesson for a Western audience: the priest and the witch—it’s the same knowledge.

Maha Dewi:

Yes, but the difference lies in how they use it—in terms of kindness and other aspects.

That’s one of the most important things my family has taught me. We should not wish harm to the witch. They have the same knowledge as the priest. It doesn’t make sense to fight against that energy. Instead, we try to bring balance with kindness.

We don’t believe in retaliation—like, if someone does something bad to me, I won’t try to get revenge. That’s not our way. We try to rebalance the energy through rituals, like offerings.

Interviewer:

I think the film also reflects this aspect of Balinese culture, at least to some extent. At first, there’s a more European reaction—the father wants the witch to die. But then they go to the priest, who tells them to calm down. Not just the father, but the whole community, which has been thrown off balance by the events. The priest gives advice to go to a holy temple in the forest, in the mountains, to bring back holy water, and then the whole community should perform a ritual to restore balance.

So this Balinese aspect is there in the film. But in the end of the film, the witch still dies. As we said earlier, it’s this mixture of European fiction and Balinese tradition—both present in the script.

Maha Dewi:

As I understand it, the witch’s death was not supposed to be the point. We don’t want the witch to die—we wait for the energy of balance to return to the soul. That’s what I’ve learned.

We see this again and again throughout the year in our many celebrations. From the small flower offerings placed on the ground to our visits to the Mother Temple—everything in our spiritual life is about regaining balance, constantly. (…) So how did the historic film come back to Bali?

Interviewer:

Louise van Plessen, a descendant of the original filmmaking team, rediscovered it. The Kinemathek in Berlin restored the film. Her ancestor, Victor van Plessen, was friends with Budiana, the famous Balinese artist. Budiana had visited Victor van Plessen, the co-creator of the film in Hamburg in the 1980s. Victor van Plessen was a close friend of Walter Spies, a key motivation for Budiana to meet him. Louise van Plessen knew about this old contact and searched for Budiana in Bali. That’s how she connected with Scott Baur, a close friend of Budiana—and then with me.

Maha Dewi:

Budiana knows my grandpa! They knew each other. Bali is a small place.

Interviewer:

Budiana knew your grandfather? Great. One of my film assistants, Yuliani, also lives in Bedulu. We’d like to show the film there.

Maha Dewi:

I hope the screening in Bedulu works out! Will the film be made available for others, or is it only shown in a closed circle?

Interviewer:

It’s copyrighted by the Kinemathek Berlin. Right now, it’s only being shown at special public events like today. But I think they may make it available online someday. Since it’s an important part of Bali’s cultural heritage, they’ll probably find a good solution.

Maha Dewi:

I hope so. Maybe it will even be shown on television one day.

Interviewer:

And you’re an artist yourself?

Maha Dewi:

I work in media—also with video. I studied it in college. I do photography too. I’m still learning, but I’ve started taking on some commissions.

Interviewer:

Thanks so much for the conversation.

(Interviewer: Joo Peter)

Coproduction of Joo Peter Studio Cinemate and Usada Ubud, Transcript and portraits photos: Joo Peter

http://cinemate.org – http://usadabali.com

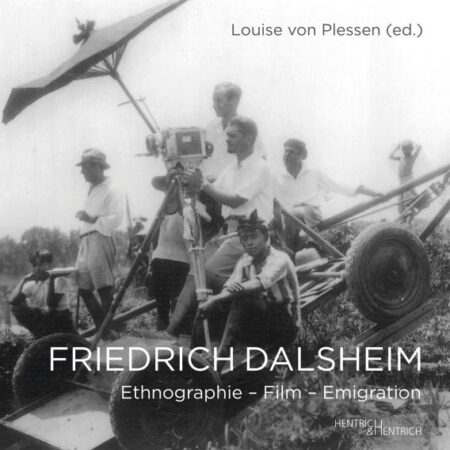

Book about director Friedrich Dalsheim and the film prodcution of “Headhunters of Borneo” 1936 by Louise von Plessen, bilingual English – German