"Dreaming in layers and layers" - a conversation with I Ketut Budiana

After the premiere of the restored film “Island of Demons” of 1933 in Ubud August 2025, I visited I Ketut Budiana as an leading artist in Bali deeply connected to traditional culture to hear his impressions after attending the screening. Budiana answered like a true master. Not directly, but with a deeper message that gradually unfolded as he moved away from the topic of the film and began speaking about his own art. His reflections reminded me of a key point of Bali culture which Putu Yudiantara mentioned during his talk at Usada: Vedic Hinduism had less influence on Bali than Tantric Hinduism, which is much more deeply connected to ancient animistic roots in Bali. Putu offered a compelling example: In Vedic Hinduism, Māyā is understood as illusion. In Tantric Hinduism, however, the concept of Māyā is more complex—it represents the diversity of incarnations of cosmic forces.

I followed up on this comments in a research and came across the following quotes: In Vedic Hinduism, Maya is the “cosmic illusion that veils the true nature of reality, which is Brahman—the infinite, formless, non-dual consciousness.” In Tantric Hinduism, on the other hand, “Maya is not just illusion, but a creative power of the Divine—especially (Śakti), the Goddess. She manifests the world, not to deceive, but to express the divine in form. The world is not something to escape from, but to engage with spiritually, using the body, senses, and emotions as tools for liberation. Māyā is real, but it’s a relative reality, an expression of consciousness (Śiva) through energy (Śakti). Instead of rejecting the world, Tantra embraces it as sacred.” Tantric Hinduism is much more an open process, allows much more the co-existence of different roots, influences, interpretations.

It can be a key to the art of Budiana and his deeper understanding of Bali culture.

As for the 1933 film, Budiana emphasized the importance of Walter Spies—both his influence on the film and on Balinese art in general. I had often wondered why Walter Spies had such a profound impact on art in Bali. Budiana, almost in passing, evoked with simple words a deeper insight. To understand his words, be reminded that Wayang Kulit, the traditional shadow puppet theatre, is so fundamental to Balinese culture. It is created by light and shadow, enigma of the spiritual. The magical surrealism of Walter Spies uses light and shadow in a new and impactful way for Balinese perspective, often in moon light night scenes of rice fields, valleys, rivers. More than physical objects, an inner light shines in these landscapes, related in its own unique way to flickering light of the shadow theatre. Walter Spies uses colors, but reduced in moon light to almost black in white. There is a transcending quality in the sensibility of Walter Spies as an artist which connects with Balinese spirit.

Traditional Balinese painting was line art. Now the moving energy of light and shadow could enter the painting. It was a huge inspiration for Balinese art. Budiana soon went beyond narrative line art and became a genius in the drama of the moving light and shadow in the powerful spiritual storytelling of his paintings. For the start of our conversation, Budiana lit incense candles and we watched the smoke rise gently while we were talking. Budiana found a way to paint Niskala.

As a coincidence, black & white film of the early 20th century also was a unique and innovate art of moving light and shadows. The production of “Island of Demons” started as a silent movie, but in the process, technology advanced and they were able to add sound and did so using natural sound and Balinese language like a musical layer, while also composing European film music responding to it.

Conversation with Budiana August 23, 2025

Budiana (sitting in the garden):

My name is I Ketut Budiana, born in 1950 in Padang Tegal, Ubud. We were four siblings. My grandfather was a craftsman, he made shrines and Balinese buildings. Including Monkey Forest—it was my father who built it, though it wasn’t called Monkey Forest back then, it was Pura Dalem Agung Padang Tegal. So, Monkey Forest only later received that name; before, it was Pura Dalem Agung Padang Tegal. My grandfather’s name was I Made Kari. He was a shrine builder, a master craftsman throughout Gianyar, around the 1900s. At the beginning, I stayed with my grandfather, the shrine builder, so I received much education there, and even though I came here later, I always returned there as a student.

Here in Ubud I met my patrons; I was always included, and that’s how my connection with Ubud grew. That’s also how I came to know many foreigners, for example Rudolf Bonnet. Indeed, Walter Spies hasn’t been there any more, but many foreigners stayed in Bali, especially in Ubud, and I met them. Through that, I was guided by Rudolf Bonnet, a Dutchman, who taught me painting. So, Rudolf Bonnet was my teacher, my painting teacher. From Bonnet, that’s how I came to know Walter Spies. I was very, very amazed when I saw the photos of his paintings. Even though I never met him in person—because he had already passed away— I was truly very amazed and really admired his works. One of them was a painting titled ‘Liak’, which is now in ARMA (Agung Rai Museum of Art). And also his creations, what was it—his gamelan music. He was the one who created the Ramayana story in performance form. Before that, there was no “Cak” dance, like it is now. It was Walter Spies who created that. That’s why I so deeply admired his works. But I never had the chance to meet him in real life— maybe at Niskala (The unseen spritual realm), hahaha. And from there, I met friends from Germany.

A friend of the Walter Spies Foundation was called Hans Joss, and he was the chairman. I visited the foundation when I went to Denmark, at a festival. I joined the festival and stopped by in Germany, picked up by Hans Joss, the chairman of the foundation. And I stayed there, in a place they called a palace, the Walter Spies Palace,

I forgot the name—there was a woman there, Victoria von Plessen, yes, that’s it. And before that, one of my paintings was brought there, the one titled Calonarang (barong and Randa fight-symbolizing the battle between good and evil). So through that I had conversations there about how the life of Walter Spies was here in Bali (…) I very deeply admired his paintings. He seemed to pass on something— yes, creating a painting that carried shadows of light, you know? That’s what I deeply admired.

(…) That young woman, yes, I met her in Germany. We both were connected through our deep appreciation of the art of Walter Spies. And in my view, there was an opportunity in this time to create a memory—like through a film or something similar— for his memory.

That was the story. But as a painter, I couldn’t accomplish a film. At most, I could support it, encourage it, that’s all.

Maha Dewi: So, when you’ve been in Hamburg, what was the most memorable story or impression from that meeting?

Budiana: Well, in Hamburg I didn’t spend too much time, because at the time I was still tied to Denmark, to that festival.

Maha Dewi: Let’s talk about the film from yesterday.

Budiana: What’s my opinion from the perspective of Bali? Well, philosophically, the film was very, very good. It served as a kind of memory, a very good memory reminding us of the past, of our elders back then. Nowadays, such things are rare, maybe even non-existent. So this film is an opportunity for the younger generation to see: “Oh, that’s how it was back then—different from now.” That’s very good, especially since many of the scenes were authentic, true to their time.

Maha Dewi: So, regarding the film, was it more of a foreign art form, or was it already deeply Balinese?

Budiana: In my opinion, it depicted the life of that time. It was framed as a story, yes, the life of that era—around the 1930s. Yes, that was the life of the Balinese people back then. So we can clearly see the difference between then and now. Back then, we remembered that Balinese people believed in ‘karma pala’ (the result of consequences; the law of cause and effect)—whatever you did, that is what you would receive. That really stuck with me. Now it still exists, but it’s a little blurred. So, in my view, the film really succeeded in portraying life—yes, indeed In the old days, yes, but now it has to be reframed so that people can better understand.

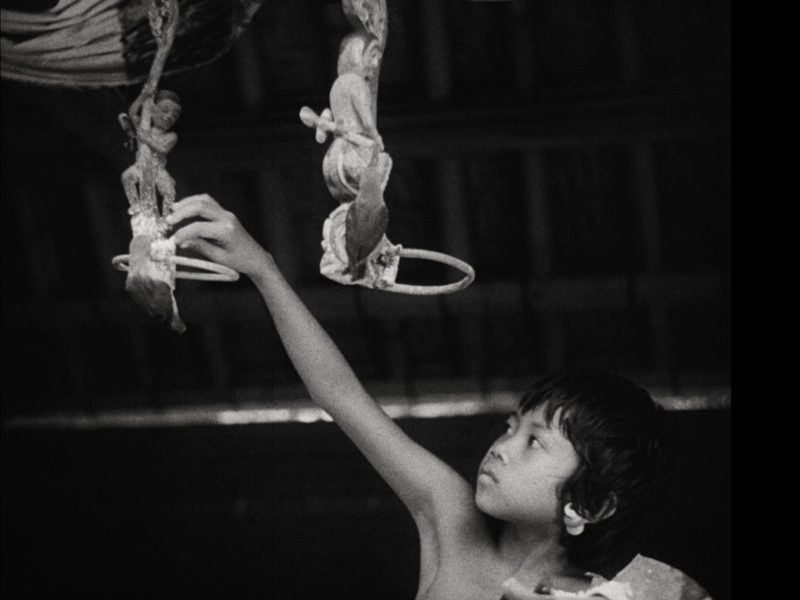

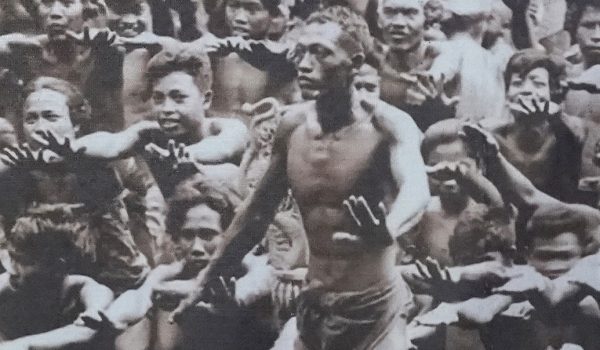

above: film stills of “Island of Demons”, 1933, director F. Dalsheim, (c) Deutsche Kinemathek Berlin

Budiana: Nowadays, especially the younger ones who have never heard these stories, they get confused, puzzled when watching. They wonder, “Why aren’t they wearing clothes?” and so on—of course they get confused. But back then, that was normal. For example, myself—in 1970, when I made a Rangda mask for the temple, when performing at the temple, I didn’t wear a udeng (headcloth), only a simple cloth wrap. At that time, it was already permitted, it was normal then. But now, people wear a headcloth, a sash, and so forth. Yes, in terms of ethics, that’s how it has developed. But back then—especially in the 1930s—yes, women’s breasts were visible. People bathed naked in the river then. But now, times are different. I was once asked by someone, a member of parliament from Jakarta, about it. Those pictures or photos of naked people were considered pornographic. But actually, they were the reality of that time. So, when someone wanted to make a film like that—depicting the past—it was protested. People said, “That’s pornographic, that’s obscene.” Well, that was part of development: the authentic was restricted. So that’s the situation.

Maha Dewi: Now, when watching the film, does it truly give a philosophical depiction of Balinese life at that time? Perhaps it needed better sound, audio, or context of the civilization?

Budiana: Yes, the sound was not clear, seemed blurred. But as for the scenes, I enjoyed them—they were very good, very good, showing the authenticity of that time. Of course, each era evolves, so it is different. So maybe, if improvements could be made in the video, I think the storyline was already good, only the audio lacked clarity. For someone like me, whose hearing is not sharp, it felt vague, unclear. I think narration also in some moments wasn’t very clear—(subtitle) explanations and so on. Nevertheless, That’s Bali. So, what is shown there is not bad, not wrong. It shows karma pala (the law of cause and effect). When someone is innocent, they won’t be harmed. When someone does wrong or bad deeds, they will suffer the consequences. That’s part of karma pala education: whoever does wrong will receive wrong, whoever does good will receive good. That’s one of the teachings embedded in it.

Maha Dewi: So from a Balinese perspective, for example, with the figure of ‘Calonarang’ (barong and rangda fight ; symbolizing the struggle between good and evil), should it be destroyed or balanced?

Budiana: It does not need to be destroyed. This creation cannot and must not be destroyed. It is a teaching: the good will rise, the bad will fall. That means in the story, the bad will be defeated. So even the bad, in the end, meets its downfall. The point in Bali is balance. Yes, balance. As I mentioned, nowadays many people tell the story of ‘Calonarang’ There is the figure of Barong and Rangda. And this represents balance. If Barong dominates too much, it is unbalanced. If Rangda dominates too much, it is unbalanced. But in the temple, they are united.

Maha Dewi: What does that mean?

Budiana: From the one, it became two and then was put into conflict. And from there arose truth— AUM, the true one, and also the false one.

Maha Dewi: In the film’s story, did Mangku (temple priest) and also Liak (Balinese mythology of witch associated with dark magic) have the same knowledge, or did they have different visions and missions?

Budiana: Actually, that was just a scene. So in the end, they became one again. That’s the proof. For example, in wayang (shadow theatre): Ravana and Dharmawangsa — they conflict, but in the palm-leaf manuscript they are written as one. This is a remarkable philosophy: from one story, it is made into different sides, but in the end, it’s still one. That’s what should be taken as the lesson. That’s why Rangda is said to be bad, while Barong is usually seen as good.But in the temple, they are united—there, Barong and Rangda are one. That is a profound philosophy. So first we must interpret its philosophy.

But nowadays, many people say that in Calonarang, there are lots of corpses, bodies. That’s fine—it’s a story. But the essence of the story is philosophy. That philosophy is balance. Rwa Bhineda (the duality of opposites).

above: film stills of “Island of Demons”, 1933, director F. Dalsheim, (c) Deutsche Kinemathek Berlin

Maha Dewi: So if we compare old Bali and present-day Bali, what should we rebalance?

Budiana: Nowadays, development has been… very, very rapid, too much development. So it has become confusing, actually, because there are too many teachings or influences coming from outside. And before we even try to understand what our ancestors taught us, we already judge it: “Oh, that’s bad,” when in fact, it is a teaching of balance. So there is no “bad,” no “good”—there is balance. That is what we Balinese should strive toward.

Now, when people talk about Calonarang, ,usually they just focus on the corpses, the death. But they miss the meaning. Maybe it’s me who doesn’t understand, but…

Maha Dewi: So, from your experience, Mr. Budiana, seeing the foreigners who came in the old days and now— what development, what understanding of old Bali still remains with you? and what have you carried forward until today?

Budiana: Yes, the Balinese terms, like Rwa Bhineda (Balinese philosophy; everything exists in pairs, good and bad, day and night, joy and sorrow and balance between them is essential in life) that must be truly understood:

two that are different, but are the same.

How do we explore more deeply the idea of different but the same? Yes, in our development we have Rwa Bhineda—but in the end, they are one. Two things that are very different, but eventually they unite. For example, as we said earlier— in wayang, in ritual, in the temple— they are all inside one palm-leaf manuscript. This must be interpreted deeply: Rangda, the temple, the sacred, and the good— still present together in the temple. Then after that comes the ritual of receiving holy water – Tirtha. This must be taken as a whole, not in fragments. Because nowadays, people tend to interpret only parts, so the meaning is off—not entirely wrong, but incomplete. That means we, as humans, and the Creator are one. Yes, but of course, we are limited by age. Life is limited, so don’t be arrogant. Hahaha.

Maha Dewi: If there’s something I’d like to pass on to the younger generation, what message would I leave?

Budiana: For me, it is: understand first what already exists. Only after truly understanding, then make a decision. Don’t make decisions first, only later looking at Rangda, seeing it as evil,

like a demon or something bad. No—first study what it really means. Why did people create Rangda with fangs like that, with her tongue like that, and so on? First understand, don’t judge right away: “Oh, this is bad.”

That, I think, is the deepest lesson.cBecause in Bali, there are so, so many teachings to be learned. One example is Hineda; two things that are different, but they are also the same. That, I think, is the message I can give. Hopefully, what (….?) has created can revive real understanding of what Bali truly is. What is Bali? If Bali could be summed up in three words, what would they be First: learn before making judgments.

Maha Dewi and the family roots of Cecak dance in Bedulu and Bona

Maha Dewi : Then, as for my background—since the film was located in Bedulu – are the artists in the film from Bedulu, or are they mixed from other villages, like Bona (where I come from)?

Budiana: In my experience, after all that— my father was a dancer, my uncle a drummer (damrat cek), and he also taught colors, and then there was my mother. From that, at the time we created the Cak in Padang Tegal, those who could perform were called (brought together). So, who would fit as Ravana? Not always from this village. Sometimes they called people from other villages.

Maha Dewi: Yes, yes, that’s true. Like my mother, she was from Bedulu. She was brought here by my father, and here she established Cak for this village. While Ravana—that role was brought in by my father from outside, along with trainers from Singapadu. So in my view, there were outside influences too— they would say, “Oh, this one fits as Ravana,” or “This one fits as Rama.” That’s how it was chosen. Back then, the famous group was Pak Limbak’s. He was truly skilled in acting and performing scenes.

So, Mr. Budiana, according to the old generation, was Kecak different back then?

Budiana: From the stories I’ve heard, yes. Before Water Spies, Kecak was only “cek-cek-cek”—just sounds, without story. In the rice fields, after harvesting, in the morning, they would gather, make noise, imitate, laugh—that was it. Only later, Walter Spies added the Ramayana story. So yes, it was closer to Sanghyang Jarang. But Sanghyang is different. Kecak is not Sanghyang.

Though Kecak borrowed some elements, it was not Sanghyang. Back then, Kecak was just playful chanting, later associated with drunkenness, fun, and so on. Then it developed after Walter Spies put the Ramayana into it.

Maha Dewi: So, Mr. Budiana, would you agree that Kecak was originally just entertainment for farmers after harvest?

Budiana: Yes—Bali is very unique. Extremely unique. In Bali, entertainment can become something sacred. That’s why now, even when creating new variations of Cak, they can still become sacred—uniquely Balinese. This is what must be understood about Bali. The feeling is like, “Yes, let’s close with this.” If there’s something missing, please add it.

What am I working on now? Maybe I’ll share a little. As a Balinese, I myself cannot fully explain what it means to be Balinese. I just followed along, making masks together—like this, yes, masks together. I made them as offerings, not for business. Recently, I made a Barong in Lombok. Yes, all of it was donation work, not for profit. So in Lombok, I have already made two Barongs, one in Rinjani and one in Mataram. It’s always like that—whoever wants it, that’s fine, but it must be done sincerely, not for business. That’s what I understood from the teachings of our elders. When someone needs something that is useful for life, if we have it, we must do it. Yes, when it comes to making statues or masks that have religious importance—offerings for temples or sacred places—that I do wholeheartedly, sincerely. That’s what we can do.

But painting is different. With painting, there are works that I keep for memory, and there are those that are sold. The process is different from making statues, like at Monkey Forest—all the works I did there were offerings. And also in Lombok, I made many statues as offerings. In Java too.

Because whatever we can dedicate, it’s not an offering to the gods alone—God is universal. It is also an offering to people, to those who understand what we create, those who understand divinity itself. That is the meaning. So that is one of the Balinese teachings still held today, though lately it has shifted—because now everything uses money.

For myself, I try, but of course not 100%. Money is always needed. But the point is—where does the money come from, and how is it earned—so that sincerity is preserved? We separate it: for Yadnya (sacred offering) and for personal needs. For personal things, like painting for memory or for sale—that is different. Again, it’s about balance.

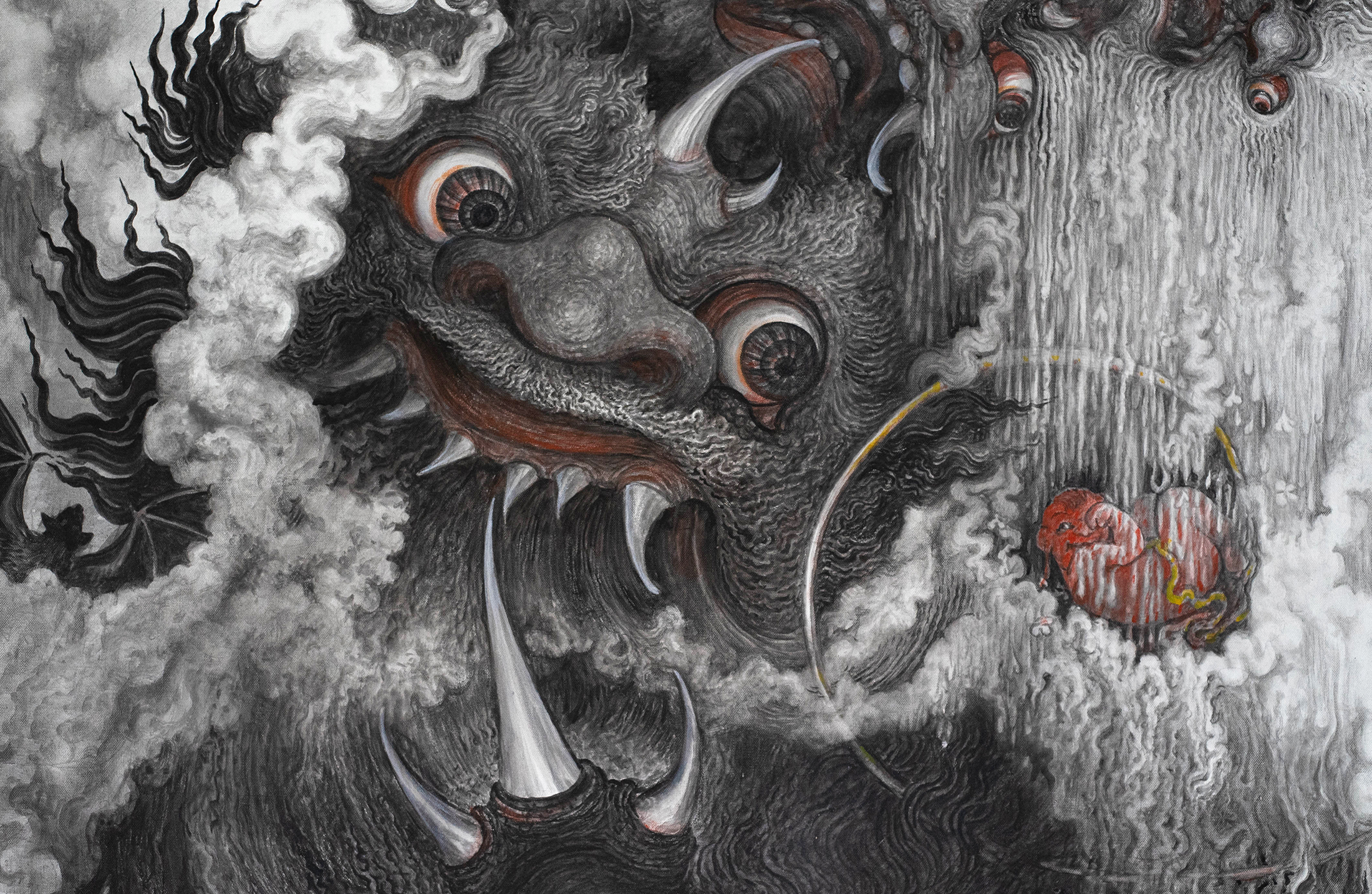

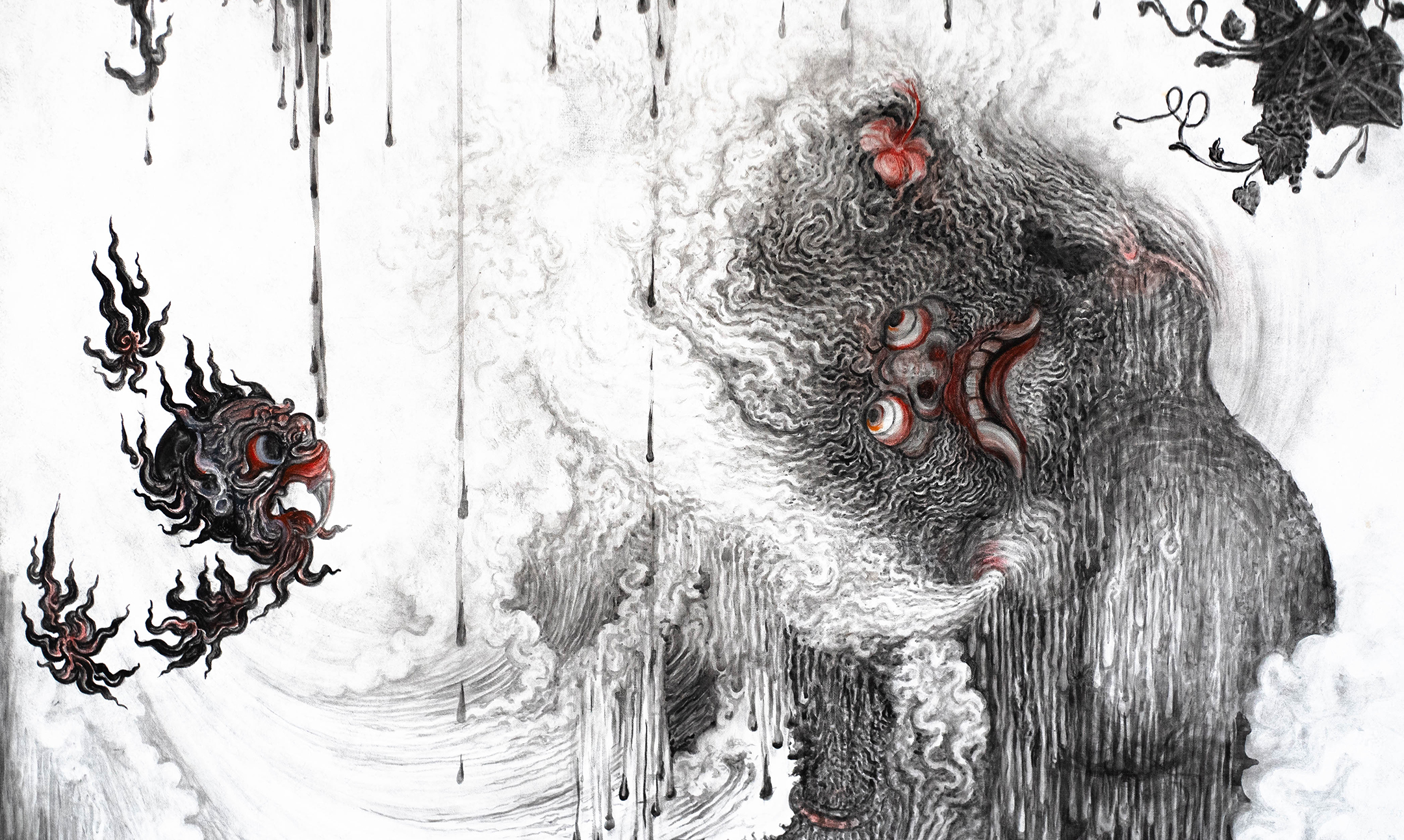

Art in the garden of Budiana

Walking through the garden towards the studio, we pass a shrine with paintings of Budiana in the connecting center of the garden.

Budiana: So here I painted Brahma and Vishnu…..it’s the old the story of arrogance: “I am more powerful.” But not Brahma and Vishnu. So Brahma said he could reach the very top. And Vishnu said he could reach the very bottom. But then Shiva tested them. And what happened? Vishnu turned into a boar, he became a boar to go deeper and deeper, but he never found the end. Brahma turned into a bird, flying upward, but he never found the end either. It’s a wonderful story.

Yes. For example, the judges wanted to show it in Ubud. Maybe things like this are not publicized enough, so many people don’t understand. But here in Padang Tegal, when a big ceremony is held, all the small elements are included. Those are placed into the ‘Kober’ (large sacred ceremonial flag, used in temples and rituals, the symbol of divine power and protection) , the offerings, the rituals, and so forth. But the explanation is often lacking— just making it, without explaining deeply.

Yes, and this one – what is this? In your view, what is this? It looks like a head, an elephant’s head. But the ears are small—pig ears, or elephant ears?Yes, it has tusks—pig tusks or elephant tusks. Actually, this is Yoga. This is kundalini: it must rise, not fall. It should rise. Some people see this as obscene, but actually it is not obscene. That is the real meaning.

What interpretation can we take from this? Yes, the elephant represents strength. It raises the kundalini. To raise the kundalini, the energy must go upward. From here, it means focusing energy so the mind can rise upward— from here, to where? Either to moksha (liberation) or to life again. That is what kundalini determines. So it plays a role, yes. People may see it as excessive or obscene, but actually— beside the shrine, it has meaning.

It also has three symbolic meanings. What are those? Yes, (…..) knows. So, all of this is a lesson. Everyone must first understand it, so they don’t just jump to conclusions — “Ah, this is like that.” Don’t judge it too quickly. Balinese teachings are all like this. In other words, Bali is the skin. Yes, but—inside, it is empty, that is the deepest part. Is it still being worked on, or is it already complete? How long does the work take? I don’t know. It depends on inspiration. Simple.

(we are going upstairs into the studio, talking about a large painting on the topic of mother)

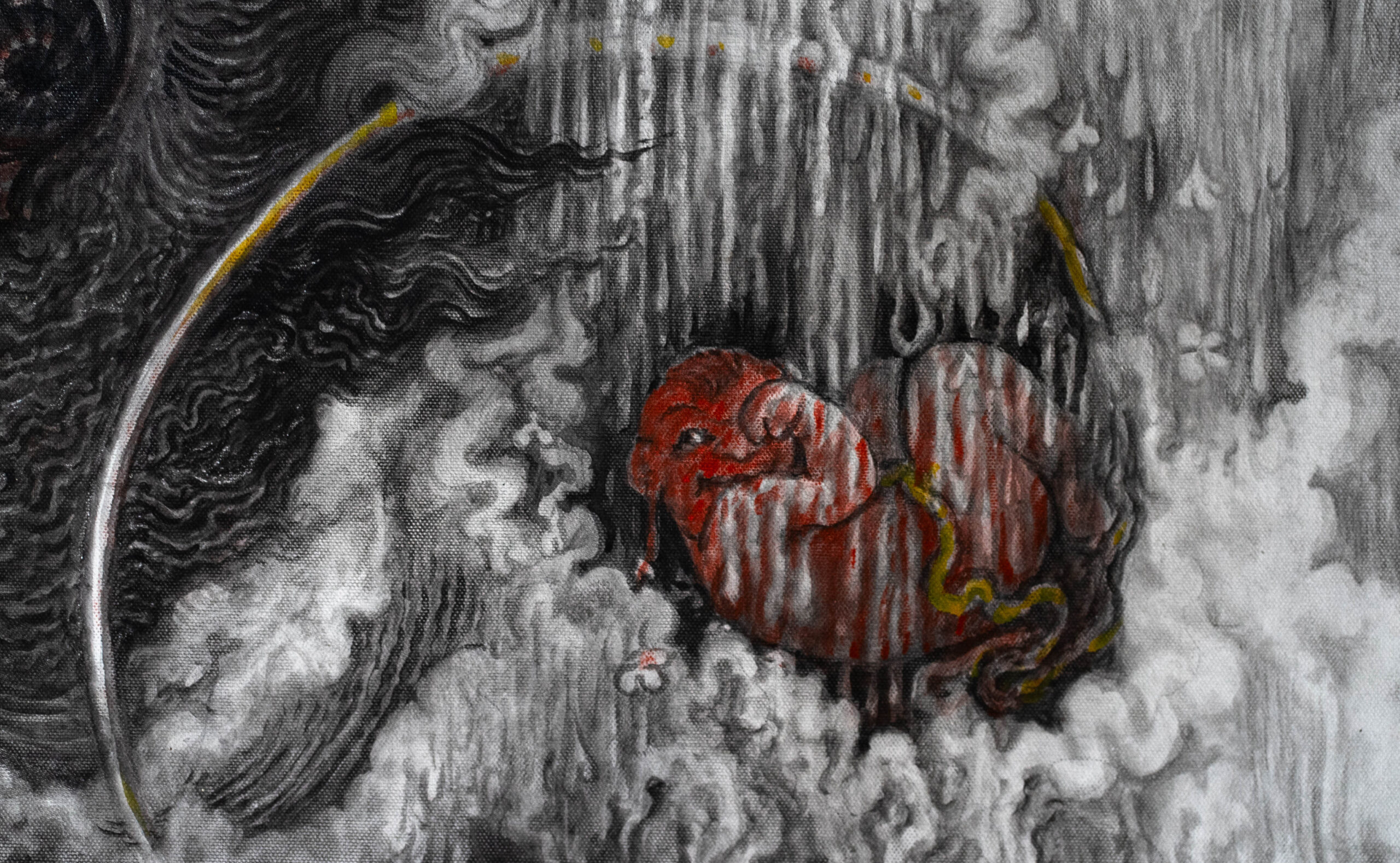

Studio Budiana

Budiana: This—this is all the strength of the mother. This, all of this, is the power of the mother. Earlier, that was rising.

This one here, its movement is upward. This one, downward.

Are they the same? Yes, this one is downward. If this is exalted, it is arrogance. Monstrosity and all of that. But all are true, none are wrong. Everything again, yes? Interpretation, perspective. There are levels of difficulty there. Because it is about feeling right, feeling wrong. But actually, there is no right, no wrong. That is perspective. Like the sixth stage, perhaps—emptiness. That is what is sought. Zero—that is what is sought. The sixth light, that is the turning. That is the turning. As long as humans exist, certainly, (Om….?) life is movement. Without movement, there is no life. Dynamic—yes, that is the dynamic of life. Yes, that is life. If there is no movement, there is no life.

It is only the body—we are the ones who give it meaning and adjust it to our abilities. Our Lord gives us a certain ability at birth. (om…?), do you have another opinion? God Himself must be understood. And we, yes, we are limited. Time is limited, right? There are complications, many obstacles. So maybe we are limited to only a few minutes. Every moment, every minute, we are limited. Like the eye—Power of the Mother. This is the strength of the mother. But truly, the mother is very beautiful. Yes, her energy—when she is violated, it is extraordinary.

Extraordinary, the way she restores balance, she holds life itself. That is within us. Mother is beautiful; we make her beautiful, very beautiful. But this is imagined as the power of the mother like this. This is what can happen in life. The mother gives birth, extraordinary. So she is the source of life. Yes. But everything goes back and forth. Life, death, life, death. Nothing is permanent in this world. Nothing. The body ages, ages, ages—then disappears. Who can stop it? It just happens. Yes, that is how life is. Meetings and partings. That’s why (….) —those are corrupt.

So perhaps, according to this teaching, Bali gives more meaning to time. Like the mother, actually. Whereas in foreign countries, there are rules, structures, fixed moments— not the same as here.

For example, Brahmacari (learning phase). Here we are directed to study—that is universal. Study anything. Learn and learn. Yes, during learning, maybe until about 100% complete.

Then comes Wanaprastha (the household phase; getting married, working, rasing a family). Wana means forest, Prastha means house (check spelling). So the house is like a base, like a forest.

After that, only then does one move from there to monkhood, to being a monk. So, in doing the practice of monkhood, Biksu, all of those women—

that means the younger, the younger sister, the grandmother, the elder—all of them are the same. That is biksu (the final stage of life; living as an ascetic or wandering holy man, renouncing all worldly attachment). Like in the wayang stories, the Pewayangan— that is it. Yes, that is Bali.

Do you understand now, how this connects with the earlier question? So, if we explain why Bali is like this— Aum – it is about Rwa Bhineda (two spirits in opposition). These are two spirits, different but one. This must exist; it is extremely important. If it does not exist, there is no life. Like father and mother, who together become one parent. That’s why in the letters Ang and Ah, when united, they create something. If they are not united, nothing arises. Yes, that is Rwa Bhineda. From the syllables Ang and Ah:

Ang (Balinese aksara symbol) is water, united it becomes Aum (Balinese aksara symbol) the seed.

That is already present in the temple— that is the symbol, the symbol of creation.

And Ah (Balinese aksara symbol) is fire.

Ah also means money, yes. This is Rachirta, Martha. In yoga, it is what lies below.

Rwa Bhineda is one, right? And from that something arises. But the real thing, the one that is pushed, that is here, that is life— that is yoga.

For example, if the will is brought downward, all the energy will dissipate and nothing will exist. That is the meaning of this philosophy. But if the habit is to bring it downward without transforming it— without passing through love (amor)— the meaning is different, deeper.

That’s why it is not pornography— it is actually something very sacred. It goes back to Rwa Bhineda. Like in yoga, where energy is moved upward— it rises, yes. If it goes downward, it becomes a child. If it rises upward, it transforms. That is why it is important to interpret it first, before misunderstanding.

Yes, in this world, all are symbols. What Ong has described—people already know. That’s why we tell it in symbols:

these symbols, these forms.

It is actually a lesson for the self: how to interpret ourselves, how to see life within ourselves. Where we will go, eventually— that is the question.

Joo Peter (suggesting interpretation to the next painting): Hanoman—he is fierce, but actually, in his heart, he is a Buddha.

Budiana: Why is he called Hanoman? Why not something else? Because it is carried in people’s memory, passed down. But this is not Hanoman —it is always about (…….?), but the energy within them.

This is a Buddhist symbol, Buddha.

Ong (?) within oneself, in the heart—that is Buddha.

This is a Shiva symbol, the outer self.

So what is this one? Our body.

Yes. So this represents our body, heart, and mind.

But now, when people see it, they just say, “Oh, Hanoman.” Too narrow. This is body, mind, and soul. So this is interpretation through the body. Not always about Hanoman.

We dream in layers. Layers and layers. It’s not more difficult—

I think it is dreaming in layers.

Layers and layers – what understanding comes after this discussion? Balinese teachings, tantra— there are Balinese lessons that are deeper than what foreigners see. In truth, Bali had other religions too. That’s why they were forced to have holy cities, temples, things like that. That’s what grew later. That’s why, if we look at statues from the past, for example in Goa Gajah, they were from before Hinduism entered.

(Next painting)

This is again Kebo Iwa (Legendary Balinese Hero). If we sum it up—without labels— that was the original Bali, wasn’t it? Yes, that’s the truth. So later, religions came, with holy books, scriptures. But can we still find that earlier understanding? Actually, in Bali before, it was Bhairawa (Protective and destructive forces) understanding. For example, my grandfather was a balian (healer). Yes, he didn’t know the mantras of Shiva. (….)

What is Mangku? (balinese priest) Mangku means to hold, to bear, to carry something. But not just like going to the temple and praying—that’s not it. No, Mangku is carrying. And there are many kinds of Mangku. (…) I forgot your name?

Maha Dewi: Maha Dewi. Mastiayu Maha Dewi.

Budiana: Maha means great. Dewi also means great. Greater than great. The most supreme.

Text and photos by (c) Joo Peter.

Coproduction of Joo Peter Studio Cinemate and Usada Ubud

http://cinemate.org – http://usadabali.com

Watch Islands of Demons: La Cinetek (German Version).

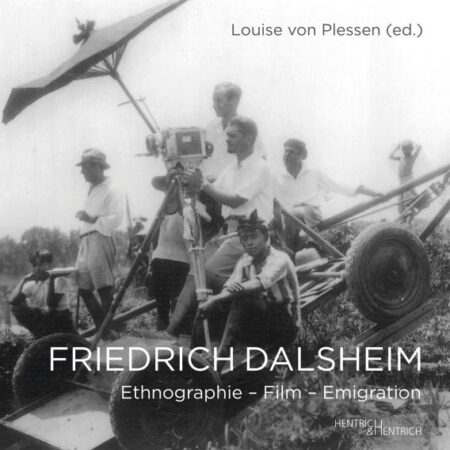

Book about director Friedrich Dalsheim and the filmprodcution of “Headhunters of Borneo” 1936 by Louise von Plessen, bilingual English – German