Looking back in time: Borneo Dayak 1936

After the national premiere of the rediscovered and restored film Headhunters of Borneo (1936) at Usada in Ubud, Bali on August 3rd, 2025, we had the opportunity to talk to indigenous Dayak visitor Cakra Wirawan Bangkan, reflecting on history and changes of Dayak culture

Reconnect with the ancestors

Joo: What is the name of your tribe?

Cakra: Dayak Ngaju.

Joo: This is central Borneo, right?

Cakra: Yes, this is central. But I went also to the area of the tribe in the film, North Borneo or East Kalimantan.

Joo: It’s the Kayan River area?

Cakra: No, Hayan River. Or Kahayan, they call it. But my tribe is in the center of Borneo. In old time, people call it Biaju. The Biaju people.

Joo: And how far away is it to this village?

Cakra: It’s pretty far away. If we want to go to Kayan, we have to go to Barito river, then to Mahakam river, then to Kayan river, so it’s quite is far away.

Joo: Nevertheless, as you said before, there are a lot of strong connections in culture.

Cakra: Yes, with the Mahakam people. The Bahau. Their culture is similar to the Kayan. We have a strong connection with the Bahau people. So if you go upstream of Mahakam, to Long Glat and this region, they speak our language. They still understand us.

Joo: You were able to identify aspects like a typical ritual in the film?

Cakra: Yes.

The shift to the peaceful goddess

Joo: You mentioned the Goddess. Tell me more about it.

Cakra: So actually, the Kenyah in Apo Kayan, before their old religion changed, worshipped a Supreme God who was male. If I’m not mistaken, his name was Jalung. But this god is very vicious. He demands war, demands many things, and they suffer for that. And there is one chief, I forgot her name. She got a dream. She met this Goddess, the Bungan Malan Peselong Luan. So since then, they started to worship the Supreme God as the Goddess — the Bungan Malan, this benevolent spirit. And then they stopped war, became more peaceful.

Joo: Has there been influence from outside, putting pressure into this direction?

Cakra: No, they didn’t have pressure from outside, because the chief I mentioned, she got something like a revelation from the dreams about this God, this Bungan Malan Peselong Luan. But after Christianity came, I can say, this religion has gone extinct. It’s gone now. Yeah.

Joo: About when was this shift to the Goddess? Around which time?

Cakra: I’m not sure about this time-wise, but we differentiate that the timeline in Dayak as time of war. So after the time of the war, people engaged more in trading, they became more peaceful. There still have been some wars, but in general it became more peaceful. I’m not sure about the time, but we differentiate this eras. The first era is Genesis, like tetek tatum (Dayak Ngaju oral epic/chant that recounts origins, ancestors, and mythic history. It literally means “cry/voice of the ancestors”). Tetek tatum means the cry of your ancestor. Yes. This was a tough time, people have been on war with each other. And after that, they’re shifting to the era of people who go for more trade relationships. And there are no more wars. In this era, there are no more stories about wars in the banjar any more. People tell a story about their success when they go trading and come back, become wealthy. So I think the film is related to the beginning of that era. But time-wise, I need to trace our ancestor who started the change. In my family history, my ancestors, the grandfather of grandmother is the last headhunter. So from that timeline, I can estimate when this change started.

Joo: Yes. That gives a pretty clear idea, generation-wise. And the goddess, tell me more about the goddess. Which context does she have? Does she come from the forest?

Cakra: I’m not sure about Bungan Malan, but in Kaharingan, the God is not in the forest. There is a spirit of the forest. There is the manifestation of God in the forest, which is part of the God in all… In the beginning, the space was like this shape (indicating a form like a handful of clay), and then God appeared, and he started forging it and it by and by expanded it. Yes. So the God is not from the forest, but it’s something above the universe. But this God is forging the universe. It just starts from this small and became big, expanded. I think now what the scientists call it, expandable universe, right? Yes. So the spirit in the forest or in the mountain, in the river is just a manifestation of the power of God itself. Yes.

Joo: And so how is the Goddess in this context? What can you tell about the Goddess?

Cakra: About the Goddess? I don’t have much reverberation, not much knowledge about the Bungan Malan religion because this religion has been gone. No more people worshiping it. Maybe some small tribe still doing it in the border between Sarawak and Indonesia. They’re part of us. I heard that… I think in the ’70s (I know that since I have a friend from Kenyah), they buried all the heirlooms from the Bungan Malan era in another place, in the sacred place. So since then, everything about this religion is gone. We don’t have much information about the rituals back then.

In the film, I can see that they ask the God, like the omens, and the God calls for peace. So this must be now the time of Bungan Malan. That’s what I understand. They stop fighting, and they bathe, clean (have cleansing rituals). Like they said in the film, after they clean themselves with the water, they will forget everything about the war.

Masks

Joo: And the other rituals, like the dance with the mask, is it something you can identify?

Cakra: Actually, the mask is actually to hide the face. The story is like this. The spirits from above, from God, came to the Earth, but spirits are so bright that people cannot see them. So they have to hide their face. They make these masks. That’s why the mask is made to cover their face, the original face of the spirit. Because if people, human beings, see the original face of the spirit, either they die or they become crazy. Because we human cannot see the face of the angels or the face of the spirit. So the spirit covers the face with the mask.

Speaker 3: I was saying that it’s Tiwah.

Cakra: Yes, Tiwah. Tiwah and Bebukung have different purposes. Bebukung is a masked ritual performance — sometimes to entertain, sometimes to frighten away spirits. But Hudoq is different: Hudoq is for agriculture. Have you seen the Hudoq Festival? Yes, Hudoq is performed to protect the rice fields and farming — it wards off evil spirits and pests. The friendly faces in the masks represent benevolent spirits. So among the Dayak, whether in Kaharingan or in the Bungan Malan tradition, you must honor both the good and the bad spirits. Why? Because the bad spirits do not exist only to disturb you, but also to protect you. And the good spirits, you also honor them — they bless you and bring good things. There must be balance between good and bad spirits.

Joo: Louise von Plessen writes in her biography of the director Friedrich Dalsheim that this dance with the mask is connected to rice agriculture?

Cakra: Yes, the Hudoq. It’s connected to the rice cult. Because this spirit is for the Tiwah ritual — to clear the path for the soul of the dead, so it does not disturb the living. And at the same time to bless the harvest. That is the purpose.

Joo: So there’s the presence of this divine power, when they protect their face.

Cakra: It keeps off bad spirits. You can differentiate from the mask. If the mask is like evil, like with the sharp teeth, so that one is to ward off the evil.

Joo: I can compare it with the tribes I met in Mentawai, Sumatra, where I shot a documentary. A lot of spirits live in the forest and at the same time, also ancestor spirits live deep in the forest.

Cakra: Yes, there is something similar… in our culture, a spirit could be like a God if he achieves some higher spiritual level. He could be what we call Nanyu. These spirits could be like a God to protect us. So we are connected to the ancestors, to the spirit of the forest, of the mountain, of the river. It’s also representation of the power of God.

The spirits are among us

Joo: Where do the ancestor spirit live?

Cakra: Among the children, their descendants. They live in the village. They build a special shrine for them.

Joo: So they are present in the village. In Mentawai, the ancestor spirits live deeper in the forest. If they are called in a ritual, they come, stay for the time of the ritual and later go back to their realm deeper in the forest. But in this case, they are present in the village.

Cakra: Yes, present in front of the long house. There is the ancestor shrine.

Joo: When the ancestors are present, that means that the communication with the ancestors is a daily experience.

Cakra: I don’t know, how it was hundreds of years ago, but now, yes, we’re still doing it. We still have our rituals (for daily communication). Yes.

Joo: It’s the same with the Bajau Laut sea nomads in Sabah, Borneo, where I just have been. The spirits are present.

Cakra: Yes.

Joo: And one of the key persons of the sea nomads I’ve interviewed, he had a more or less daily communication with the spirits, for example in his dreams.

Cakra: Yes.

Joo: That’s fascinating. So the dreams are important for your culture?

The spirits come in our dreams

Cakra: Yes, dreams are important. And also it is believed they can appear right in front of your eyes. Not any more today, because nowadays, the Dayak people are also absorbing other cultures which for example eat dogs. Then the spirits go away. They don’t like people eating dogs or doing bad things to dogs. Because according to our belief, dogs are friends for the humans. So if people start killing dogs or eating dogs, this spirits go away. They don’t want to stay. Because the smell is bad for them. That’s what I know.

Joo: When I was interviewing one of the shamans in Mentawai, he also told me that the spirits don’t visit him so much anymore, especially in the sense that he can see them. That’s not so much happening anymore.

Cakra: Yeah. Because nowadays people are going to the shrine, to ask for something, and then they pay, they’re giving the sacrifice, but that’s it. There’s no more a deeper connection like in the old times. It used to be a relationship with the spirits like friends. I heard the story of my grandmother, how they call their spirit. They call them as a friend. Sahabat, we call it. Yeah. So it’s not contractual like, for example, I ask you, I pay you this. But we make a friendship with the spirit. That’s what we call it sahabat. It’s your relationship. As a friend.

We are orphans

Joo: Can there be something like a curse — that some ancestor spirit has bad intentions also? Is it occurring?

Cakra: If there is agreement between our ancestor and the spirit. In such a case, if we’re neglecting the agreement, the spirit that should protect us now becomes angry. Some people believe that. And it could happen, because there was an agreement made before that, between our ancestor and us. And there are stories that I heard and I encountered some of them. In my family also, they got sick or had bad luck after they broke the promises.

Actually, if they want to dissolve the promise, they can do it in a proper way. How can they do? It is like a divorce, you have to communicate it with the spirit. You not just run away, right? Because first you make an agreement, there is a ritual in which you convince the spirit to become your friend, and now you want to dissolve the connection. You cannot just go away. You need to do something. You need to talk to them and explain it, for example, I want to follow another religion. I cannot continue our connection. And you tell it in a good way, not just run away.

I think they can understand it because we believe that the spirits call us humans Talatah Nulun. Talatah Nulun means we are like an orphan. They see us like an orphan that needs their care, needs their mercy.

Ask the spirit for permission

Joo: Yes, I understand. You need this connection, because in old times all the cultural knowledge is came down from the ancestors. So you search this spiritual connection to the ancestors.

Speaker 4: Yes. It’s similar to when they cut a tree. If they’re going to cut a tree, it has to be a ritual.

Cakra: Yes. Even for us to take medicine from the tree. We ask for permission. Just as you ask your friend. When we take medicine from the forest, we bring salt, we bring some nails, and we talk to the trees. I want to take a part of you, just a little part of you, not to cut you completely, not to kill you. I just take a piece of your bark for medicine for this people. I have to mention the name of the people to whom I want to give the medicine.

So I ask permission from the spirit of the Earth, the spirit of the trees, the spirit, many spirits. Yes. They call it the prophet of the Earth, the prophet of the trees, the prophet of the river, they call all for permission. This is my offering what I give you to replace what I take. They put salt, they put their nails near the trees, and they take it. Just enough what they need.

Guardian statues and carvings

Joo: And the artwork in the film, there were these statues.

Cakra: Yeah, Guardian statues.

Joo: And there were elaborate paintings on the inside of a warrior shield used in ritual dances. And also elaborate paintings and carvings on the door.

Cakra: The door was a very elaborate carving.

Joo: And do these special artworks have a specific meaning?

Cakra: Yes. In case of the carvings at the house, there are special carvings for the noblemen, which means, you cannot have it for the common people, because otherwise it will curse you. One of the common motifs, that one with the tongue out, is for protection. Or the dragon… also called aso. It’s like dogs or a dragon to protect the house. And there are motifs we call Tantalilawai (Tali Talino?). I cannot describe it. It means it’s connected from your ancestors down to you as their descendants. All the knowledge or the blessing is connected to you.

There is a carving, we call it Tali Liliwan or Bajakah Lili. It’s inspiration from the plant. I don’t know it in English. So this Bajakah Lili it’s connected, intertwined. It never, never stops. So it means from your ancestors coming down to you without interruption. Yes. All the knowledge, all the blessings. So there are many special carvings with special purposes. It also depends on the social level, whether nobleman or common people.

Joo: And so these statues have been Guardians.

Cakra: Yes, Guardians. You can still see it in Ma’anyan. BUT I think it’s gone now in most places.

Speaker 3: When we stopped in those remote villages, they had those carvingS still at the entrance to the village from the river when you got off the river. Exactly like in the film.

Tattoos & more

Joo: And the earrings, did they have a special meaning?

Cakra: No, it’s just like a fashion. It’s fashion.

Joo: And the tattoos?

Cakra: Concerning the tattoo, there are several meanings. If you are a weaver, carpenter, or doing carvings, or if you have been beheading people, also several meaningS for that. If you’ve been travelling for a long time, you get a specific tattoo. It means you have travelled, go out from your village and come back safely. So there are several meanings. Depending on the tribe. But not all the Dayaks have tattoo. It depends on the Dayak tribe.

Dayak and Punan – a common history

Cakra: Concerning the Punan — the Punan live in the forest, in caves. But their culture still is deeply connected with our tales. Before the Dayak knew the longhouse, they also live in caves. So they knew it from — how to say — the spirit, like the gods — they learned how to make this longhouse and farming from the gods.

Story of creation

Joo: Yes, this goes back to stories of creation. You mentioned, in the beginning, God modelled the universe out of something small.

Cakra: We call it Sulau, as big as Sulau, just like something very small. And God appeared and forged it like a blacksmith, forging it until it expanded and expanded. And then the universe was created. Then comes the story of the Tree of Life. There was chaos between the female bird Enggang, and the male Enggang. And from that chaos came the planets, because the fighting in the Tree of Life produced the sun, the stars, and the planets.

Joo: Yes. And how do the animals and human beings come into existence?

Cakra: Every Dayak group has a different story. In our Ngaju tradition, humans were created from the Tree of Life. We have three brothers: Raja Sangiang, Raja Sangen, and Raja Bunu. We are the descendants of Raja Bunu. The other two are like heavenly beings, our elder brothers, but they do not die — only humans are destined to die. That is why we are mortal. But they are still our siblings, and we can call on them to help us. And then, from the Tree of Life’s creation, came the planets and life. That was the beginning of life. But after that, God created humans. So there are three brothers: two dwell in the Upper World, while we live here on Earth, destined to die. To return to be like them, we must perform rituals. After death, people undergo the Tiwah or Ijambe ritual, to purify the soul so that it may join the siblings in the Upper World.

Joo: Yes. And what’s the name of the Tree of Life?

Cakra: Batang Garing. It’s the Tree of Life.

Joo: Is there a specific location?

Cakra: No, it’s in the space.

Joo: I mean in the sense that you say that the human world is, for example, more like on the roots or the center or the top of the tree of life.

Cakra: This is before the human world was created. When the universe was created.

Joo: When God forged and expanded the universe.

Cakra: And then there’s the Tree of Life. It’s like something in the universe. They call it the Tree of Life. And there is a chaos that created the sun, the stars and ant the planets, and after that, life was starting.

How to show love?

Joo: In the film, did you notice something where you think, oh, this is so European? It’s not really the Dayak culture. Did you notice something which maybe is more fictional? For example the love story?

Cakra: No. The story of love there is very common in our culture. But surprisingly, we don’t have words to say love. Mostly, we don’t have words to say love. We just borrow the words from Malay. But we don’t have words to say love. We don’t have words to say thank you. Because love or thanks is not shown by words, but by deeds. They have to express it. Like the story in the film, the main character fought for his love, although he had to abandon his position as a chief.

Joo: So you have to express it by action.

Cakra: Yes. Maybe this is not so romantic because we cannot express it in words.

Doubts about child marriage

Cakra: There is one thing I noticed from the movie. See, they were betrothed when they were young, maybe 12 or 13 years old. But there is no marriage at a young age in our culture. Among our Dayaks from the old times, we have no culture of child marriage. Because the male has to prove himself — that he is worthy, adult enough to provide, to build a family. So there is no story of child marriage among the Dayak people. Maybe in other parts of Indonesia there are people practicing child marriage, but in Dayak society, generally, they don’t do that.

Social classes and marriage

Joo: I wonder if this is more a European perspective: the film shows a typical love story with jealousy and so on, also violence because of jealousy.

Cakra: That’s common. Very common, even until today. Yes. But even if you go to the Ma’anyan people, or in my tribe, there are stories like that — about love, and that you cannot marry outside your equal status. The punishment could be death. Yes. So until today, even among the Kenyah people, they still trace lineage: who is a descendant of the noble line. They call it the Hipuy — the nobles, the kingly class, as opposed to common people. They cannot intermarry, even until today.

Joo: To keep the social status, you have to marry in your social class.

Cakra: In my tribe this is gone, because once they accepted Christianity, people don’t really trace about their lineage in that sense, whether you are descendants of the noblemen or the slaves.

Joo: So there have been noblemen and slaves. Has there been a middle class or other classes?

Cakra: Yes, there is a middle class. And we have Utus Gantung (correct term would be Paren?), the noblemen, and then the common people, and the slave called Utu or Jipen. This you cannot marry. But there are two types of slaves. Slaves because of debt, or slaves because you lose in the war. When you’re a slave because of debt, you can become independent if you’re able to pay your debt. So, even if you are noblemen, you can be a slave also, if you have debt.

Joo: I remember the Toraja in Sulawesi, there it was also like that in the past, noblemen and slaves, and sometimes, when they are gambling and lost a fortune, they became slaves because of the losses in gambling.

Cakra: Yes, something like that. So even if you are noblemen, you could still be in the lower class if you have a debt, but mostly they haven’t been.

Joo: Yes. And the slaves have to do more work?

Cakra: Work, yes. They get salary, but not much. They have to be able to pay for their debt, for their loan. (…)

Slaves were the first to become Christians. But the first chief who converted to Christianity — he did it not because he was a believer, but to match the power of the sultan. The Sultan of Banjarmasin was too strong and was a bully against both the Dayak and the Europeans. I think the missionary had been captured and decapitated by the sultan’s army. So the chief — his name is Tamanggung Ambun — he was the first chief in my tribe to become Christian.

He did it to counter the power of the Sultan. So they merged with the Europeans — not because they wanted to become Christian, but because “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.”

At the time, the European missionaries were the enemies of the Sultan. So they had to choose a side.

Rank of a chief

Joo: It’s quite interesting that the main character in the film playing a chief was a chief himself.

Cakra: Yes. He became the main actor. And also in Dayak, if you’re chief, your son does not necessarily become chief, will not necessarily replace you. It’s not something like that. This child has to prove that he’s worthy to become like his father. If he’s not worthy, the community can choose another chief. It’s not like because you’re the son of the king, you will automatically become chief. He needs to prove it. He needs to endure the pain. They show some rituals related to it in the film. Now, they’re still doing some of this rituals.

Intermarriage

Joo: How are the rules for marriage? Can you marry in your tribe, or do you have to marry someone from another village?

Cakra: Yeah, as long as it’s not your cousin. All the family will come and discuss: Do you have a family connection or not? Because although we have the same age… sometimes this girl can be my aunt or my nephew, and we cannot marry. If we break the rules, the punishment is that we have to eat in a place for pigs. So we will be considered like pigs.

Women and equal rights

Joo: You mentioned the shift to the goddess. How is the relationship of the genders — like women rights?

Cakra: Yes. In my tribe, the women — although they are mostly in the house providing food — can also appear as chiefs. There is a story of Nyi Balau. She was a female chief who protected the village and fought against headhunters. And also Nyi Udang. So we have female leaders. You can find equality in these aspects. For example, if your father passes away, the heirlooms are shared equally. It doesn’t matter if you are female or male.

Hunters and farmers

Joo: You have a rice culture, but you also go hunting once in a while.

Cakra: Yes, that’s true. Among the Punan, they practiced hunting and gathering. They mostly used the blowpipe and spear. But later, with the shift to settled rice farming, people began using the machete — the mandau — to open the rice fields. Even the mandau reflected social status: there was one for noblemen and one for common people.

Rituals for coming of age

Joo: Many cultures have special rituals for coming of age.

Cakra: Oh yes, there is. In my tribe, they practiced it in Kaharingan, the old religion. The Iban are still practicing something similar, like a baptism. They bathe the baby in the river, and they sacrifice a pig. The blood goes into the river, and then they bathe the baby.

Following the old belief

Speaker 3: Are you Kaharingan again? Do you follow Kaharingan?

Cakra: I’m practicing it to some extent.

(showing some photos on the smartphone) We are reading the heart, the omens in the heart of the pigs.

Joo: This is at your village?

Cakra: Yes.

By the way, now I’m working in Saudi Arabia.

Speaker 3: What are you doing in Saudi Arabia?

Cakra: Working in the oil fields.

Speaker 3: So how do you have all this knowledge?

Cakra: I come from the villages. I have my family that’s still Kaharingan. My aunt’s still is Kaharingan. But most became Christian.

About dreaming — yes, I get encounters with the spirit, the ancestors’ spirits.

Joo: You meet the spirit?

Cakra: Yes, I met. And I asked people to draw it, paint it, and they made paintings about it.

Joo: What’s the painting like?

Cakra: Hold on, let me search a photo…

See, this is the painting.

Joo: That’s great.

Cakra: This is the shrine of the ancestors. So I met this spirit. He gave me some sign.

Joo: Yes, living together with the spirits. It perfectly makes sense — in a culture with oral tradition, it’s direct communication, generation to generation, passing down knowledge. You search for connection to your ancestors.

Cakra: Yes. I see them in my dreams. I’m not familiar with the ritual things. The spirit explained it in a simple way I could understand. I talked to an old guy — they told me what it meant and what to do. I just drew it. I didn’t know the name. The elder explained what it meant, what I had to do.

It helped when my mom was sick. Before she got sick, I had this dream. They gave me signs: this is the medicine. This is what you have to take.

And I didn’t know, but they explained it in simple words. The ritual the ancestor showed me in the dream used special words I don’t understand. I went to the elders, they understood and explained it to me. “You make it like this. That is the name.” And I used it, and my mom healed.

Music

Joo: And the music — unfortunately, not so much traditional Dayak music in the film, but at least some.

Cakra: In the movie, there was some sape music that I heard, but not for rituals. Because for rituals, you use only the two-string sape. Not like today, with five or seven strings.

Taboos

Joo: Louise von Plessen also mentioned special taboos. They went upriver, and then a bird flew in the wrong direction.

Cakra: Yes. If a bird flies from right to left, that’s not good. Left to right, that’s good — an omen. Also snakes — they are an omen. Bad omen if it’s the wrong direction. Good omen if it goes to the right side, from left to right.

Speaker 4: Yes. I feel it’s like when a tree falls down.

(searching a video on his phone) I will find a video when they do the ritual.

You have to do the ritual — they call it Weheya. Maybe we will do that next year. You have to stay in front of the longhouse for three days. You cannot sleep. You must fast. You cannot be touched by a woman.

In Weheya, they still practice it very strictly. You have to keep the fire in a small hut. You just stay there. On the third or fourth day, they go hunting for a head. After that, they do the celebration. The women welcome you. They are still doing it.

In the old days, if you didn’t do this, you could not marry. You must follow this ritual as a man.

And for the feathers: it depends how many times you have followed this ritual. If you have done it many times, you can wear more feathers. If only once, one feather. If never, you cannot wear feathers at all.

The hornbill and remote relatives: the Naga in India

Speaker 3: Just another subject — have you heard of the Naga people from Nagaland?

Cakra: Nagaland, yes. In India. I have one of the swords from the Naga people. They call it a Dao. We call it Mandau, they call it Dao.

Speaker 3: There are a lot of similarities between the Naga people and these tribes. It’s amazing.

Joo: Yes. Oh yes, and they worship the hornbill, too.

Speaker 3: They even have a festival over there called the Hornbill Festival.

Cakra: Yes. And that’s true. Because the hornbill represents the upper God, while the lower God is represented by the serpent — the great snake — called Jata. Jata is the underworld God. But actually, they believe the two are one — like masculine and feminine aspects of the same God.

Joo: The snake is the feminine?

Cakra: Yeah, the feminine. And the hornbill is the masculine.

Both are divine. We humans are in the middle. They’re represented by the hornbill feather: white, black, white. That’s why we use it.

Joo: And the snake is represented also in a symbol?

Cakra: Yes. You see the carving of the dragon or aso, or of a crocodiles — it’s the underworld God.

Joo: And the black and white has a meaning?

Cakra: Yes. Because we are human — the black color. We are in the middle. That’s our world.

Joo: The Bajau Laut sea nomads also know two main deities — the Lady of the Forest and the Lord of the Sea. It’s male and female.

Cakra: Actually, if you see the Kaharingan mythology, they said that when God created humans and the earth, everything — when he looked down to the earth, he saw his shadow. That shadow is the underworld God, actually — the shadow of God.

Reviving traditions

Cakra: We do lots of exhibitions about the Mandau. In Malaysia we also held exhibitions. We try to revive the blacksmithing tradition in Borneo, because nowadays it’s almost gone — how people once made iron and forged the Mandau. Now we try to revive it. I have a friend who can do traditional blacksmithing.

Joo: Yes. Traditional blacksmithing is also in my film about Bajau Laut.

Cakra: Yes. We try to revive it. We have some short movies — like from the beginning, the raw material. We do the rituals before forging. We forge it, carve it, and by and by it becomes the sword.

So it’s a very long process to become a special sword.

(showing a ritual on his smartphone)

This is called the ritual Habay.

Habay is calling the spirit of the dead who died unnaturally — like by murder or something like that. They need to ask and “interview” this spirit — how did you die, who killed you — they will call the spirit to answer. This is my friend’s family ritual. So they make a statue or effigy, and they will call the spirit of the dead person to enter it. And then they will ask how he died.

Joo: It’s a dance ritual?

Cakra: Dance, yes. That music is for rituals.

It’s only two string.

Yes. I have a community for the youngsters in West Borneo, Central Borneo, and East Borneo. We do a lot of exhibitions for swords because we like blacksmithing and traditional swords.

Interviewer: Joo Peter. Joining the conversation: Scott Baur, David Metcalf and visitors of the screening. Film stills by the film “Headhunters of Borneo” 1936, director Friedrich Dalsheim (c) Kinemathek Berlin.

Transcript and portraits photos by Joo Peter.

Coproduction of Joo Peter Studio Cinemate and Usada Ubud

http://cinemate.org – http://usadabali.com

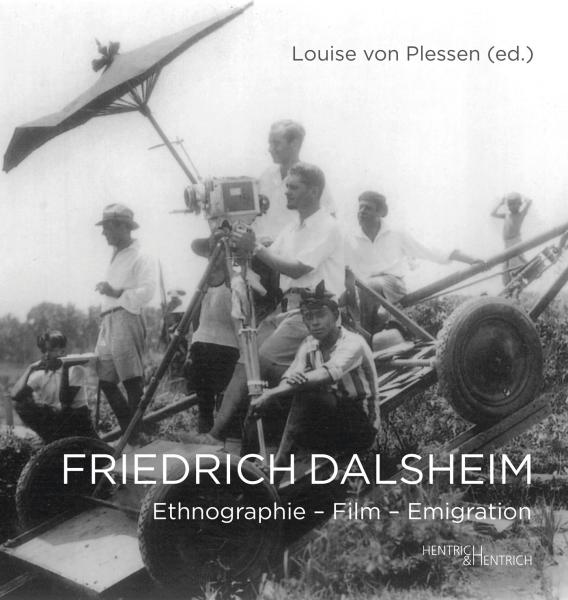

Book about director Friedrich Dalsheim and the filmprodcution of “Headhunters of Borneo” 1936 by Louise von Plessen, bilingual English – German

Glossary

Creation & Cosmology

- Sulau

Primordial speck or seed of space.- God appeared on it and expanded it like a blacksmith forging metal.

- From this act, the universe grew.

- Batangaring (Tree of Life)

Cosmic tree at the center of creation.- Site of conflict between male and female hornbills (Angang), whose struggle gave rise to the sun, stars, and planets.

- Origin of life, humans, and spirits.

- Angang (Hornbill, male/female)

Cosmic bird.- Its duality (male/female) created chaos that shaped the cosmos.

- Later venerated as the sacred bird symbol of the Upper God.

→ Cross-ref: Hornbill, Jata.

- Raja Sangyang, Raja Sangen, Raja Buno

Primordial brothers born of the Tree of Life.- Raja Buno: mortal ancestor of humans.

- Raja Sangyang & Raja Sangen: immortal siblings dwelling in the Upperworld.

- Humans descend from Raja Buno, but retain kinship with his immortal brothers.

Deities & Spirits

- Jalung

Old male god of war and blood sacrifice.- Rejected after people suffered under his violent demands.

- Bungan Malan Peselong Luan (also Pasulungluan)

Benevolent goddess who replaced Jalung in the Bungan religion of East Kalimantan.- Symbol of compassion, peace, and an end to warfare.

- Full title emphasizes her role as “bringer of peace.”

→ Cross-ref: Jalung.

- Hornbill (Burung Enggang)

Sacred bird representing the Upper God and sky principle.- Protector of communities and symbol of leadership.

→ Cross-ref: Jata.

- Protector of communities and symbol of leadership.

- Jata

The great serpent or dragon of the Underworld.- Associated with water, fertility, and feminine principle.

- Paired with the hornbill in cosmic duality (male/female, sky/earth).

- Apo

Dragon-like figure (sometimes conflated with Jata).- Appears in carvings as protective, fierce presence.

- Baliu

Spirit of the forest.- Powerful but not necessarily evil. Represents wild nature.

- Kalali (Kajali, Kalali)

Forest spirit with grotesque face.- Frightening but not malevolent; serves to drive away devils.

- Nunu / Nini

Ancestor spirits elevated to divine status through spiritual achievement. - Sahabat (“Friend spirit”)

Spirits befriended by humans.- Relationship is intimate, based on trust and respect, not contractual offerings.

- Tarantang Nulai (“Orphan Human”)

Expression of Ngaju cosmology.- Humans seen as spiritual orphans needing divine care.

- If ancestor agreements are neglected, humans become “orphans” exposed to misfortune.

Rituals of Life, Death & Balance

- Tiwah (Ngaju)

Secondary burial ritual.- Exhumation of bones, purification, reburial in sandung shrine.

- Ensures the soul’s safe journey to the Upperworld.

- Habay (Habai)

Ritual to summon the spirit of someone who died unnaturally (murder, accident).- Spirit enters an effigy and is questioned about the cause of death.

- Weheya (Kenyah/Kayan initiation)

Male initiation rite marking adulthood.- Includes Hisang (ear-piercing), fasting, fire-keeping, seclusion, and symbolic headhunting.

- Determines eligibility for marriage and right to wear feathers.

- Hisang

Ear-piercing as initiation.- Part of the Weheya ritual, symbolizing maturity.

- Tatua / Tetek Tatum

“Cry of the ancestors.”- Mythic primordial age of struggle and warfare.

- Marks the beginning of cultural history before peace and trade.

Symbols & Carvings

- Tantalilawai (Tante Lilaway)

Carving motif symbolizing continuity between ancestors and descendants. - Bajakah Lelek

Carving motif inspired by climbing vine (bajakah).- Represents resilience, growth, connection.

- Aso (Dragon-dog)

Protective carving motif.- Hybrid figure combining features of dragon and dog.

- Guardian statues

Wooden statues placed outside homes or villages.- Serve as spirit guardians, still visible among some Dayak groups (e.g., Ma’anyan).

Masks, Music & Performance

- Bebukung

Mask dance performed for entertainment and comedy.- Unlike Hudoq, not agricultural but social.

- Hudoq (Hudo)

Mask ritual tied to rice cultivation.- Grotesque masks drive away evil spirits and protect harvests.

- Tiwa in Bebukung

Another mask tradition, blending entertainment and ritual. - Sape (Sampe, Sapeh)

Traditional plucked lute.- Ritual version: 2 strings only.

- Modern form: 5–7 strings, used in performance and popular music.

- Sape Karang

Specific sape style mentioned by Cakra, played by Bahau musicians.

Weapons & Tools

- Mandau

Traditional Dayak sword, used in war, ritual, and as heirloom.- Symbol of male status and identity.

- Noble vs. common versions distinguished by ornamentation.

→ Cross-ref: Dao.

- Dao

Sword of the Naga people (Nagaland, India).- Functionally and symbolically parallel to the Mandau.

→ Cross-ref: Mandau.

- Functionally and symbolically parallel to the Mandau.

- Blowpipe (Sumpit)

Hunting weapon used by Punan.- Wooden tube with poisoned darts.

Tribes & Peoples

- Dayak

Umbrella term for indigenous peoples of Borneo. - Ngaju (Biaju)

Dayak subgroup in Central Kalimantan, associated with Kaharingan religion. - Kenyah

Apo Kayan highland group (East Kalimantan/Sarawak). - Kayan

Dayak group along the Kayan River, culturally close to Kenyah and Bahau. - Bahau

Dayak group of the upper Mahakam River. - Ma’anyan

Dayak group of Central Kalimantan, noted for unique traditions. - Naga

People of Nagaland, India. Historically headhunters, worship hornbill.- Compared with Dayak during interview.

Places & Regions

- Palangka Raya

Capital of Central Kalimantan. Speaker’s home. - Mahakam River

Major river of East Kalimantan, inhabited by Bahau and Kenyah. - Barito River

Central Kalimantan river, core of Ngaju settlements. - Apo Kayan

Highland plateau, heartland of Kenyah/Kayan peoples. - Sarawak

Malaysian Borneo, linked to Kenyah/Kayan migrations. - Nagaland (India)

Homeland of the Naga people, compared with Dayak.